headman

Rupert’s Land

Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) discouraged and kept Christian missionaries out of company territories to mid-1800s as it was seen as being a threat to their business plans where the fur trade made profit for the company.

Connection to the land, believing everything in nature possesses a spirit and practicing spirituality often involves ceremonies, storytelling and the wisdom of elders to preserve teachings on how to communicate with the spirit world. This is what characterized First Nation people when (both French and British/Scottish) fur traders met and started building alliances with them to secure trade relationships and gain access to European goods.

Native men at that time, primarily served as the skilled hunters and trappers but it was the women that traders quickly recognized could not survive without them because of their essential skills. Marriages started to become important strategic alliances and led to the creation of distinct Métis communities. Ultimately, fur traders once married, realized that their Christian faiths must be incorporated with First Nation spiritual beliefs and traditions.

Black Robes

Methodist were the first missionaries that arrived in 1840 at Pigeon Lake (Central Alberta) and the Roman Catholic Oblate missionaries followed them and arrived in 1847 to Upper Bow River.

Upon the arrival of the missionaries, Cree (Piché) and Nakoda (Assiniboine) utilized in winter and summer a vast expanse of territory for traditional hunting in the foothills of the Rockies between Upper Bow River to the to the Northern Saskatchewan watershed and they already had complex governance systems based on kinship. Missionaries started interacting with these structures and using them for their own ends.

The Cree (Piché) system historically supported the role of band chiefs who were recognized for their skills as warriors, hunters, and leaders.

Nakoda (Assiniboine), whom Stoney separated, organized their society around a band structure with the principle of passing leadership status from father to legitimate son.

From the beginning the missioner's perspective was to establish cultural and religious superiority over Cree (Piché) and Nakoda (Assiniboine) without trying to understand or appreciate their way of life and their spirituality. Working in tandem with colonial governments they imposed their authority and culture through institutions like residential schools and played a significant role in shaping the environment that led and influenced them to sign the treaties (Stoney).

Stoney

Before signing the treaties, the Nakoda (Assiniboine) were led by three principal chiefs: Chief Jacob Bearspaw, Chief John Chiniki and Chief Jacob Goodstoney.

The Methodist mission at Morleyville, established by Reverends George and John McDougall in 1873 near the Bow River (Canmore) that was located within the traditional hunting grounds of the Nakoda (Assiniboine) people. The missionaries had a specific interest in having the reserve established adjacent to their mission because it made it easier to concentrate on population for the purposes of Christianization and colonization.

In 1877 on the advice of John McDougall, the three Nakoda (Assiniboine) principal chiefs signed the treaty and Morley Reserve was established but many members refused to stay on the reserve and under the leadership of Peter Wesley moved north to the hunting grounds on the Kootenay Plains, located in North Saskatchewan River Valley where in 1948, the Big Horn Indian Reserve No. 144A was formally created.

Piché

In general, the Piché name is associated with both First Nations (Cree, Dene) and Métis communities across Western Canada. Historical records often show individuals and families with French-Canadian names, like Piché, having mixed Cree and Dene ancestry but it is the Chief Louis Piché family line that is associated with traditional hunting grounds between Upper Bow River and Northern Saskatchewan River watershed.

Once Blackfoot (specifically the Peigan) moved out from Kootenay Plains, this region became a shared area used by Cree (Piché) and Nakoda (Assiniboine) until it flooded in 1970’s.

Chief Louis Piché traditional hunting grounds covered are from Kootenay Plains south to Upper Bow River. Hudson’s Bay (HBC) often hired Chief Piché as a guide or hunter. In 1841 Piché guided the governor of the HBC, George Simpson, on his visit to the Canadian Rockies. In his honor, the governor named the lake where the band stayed as "Lake Peechee". This lake in modern days was renamed by Parks Canada and is known as Lake Minnewanka and the nearby mountain bears Chief Louis Piché name (Mount Peechee).

Chief “Bobtail” (Cree name: Keskayo) was the first son of Chief Louis Piché and his mother's name was Opeh-tah-she-toy-wishk (a Plains Cree woman). His younger brother’s name was Baptiste “Ermineskin” (Cree name: Sehkosowayanew). Their third son Joseph was killed in Upper Bow River Valley.

In around 1860, Chief Bobtail was recognized as the Head Chief (Piché) Band. Under his leadership the group continues to use their traditional Rockies hunting grounds located in Rockies foothills. For social and spiritual purposes, they gathered near the Pigeon Lake, in the Muskwacîs area ("Bear Hills" /Hobbema) for their social and spiritual gatherings.

Ka-mayahkamikahk (When Bad Things Happened)

Frank Oliver was an Edmonton’s newspaper publisher, and a Liberal politician who in 1881 start lobbying government to have “Bobtail People” removed from their reserve lands in Muskwacîs area ("Bear Hills/Hobema”) for the European settlement ( in 1911 Indian Act amendment, known as the "Oliver Act," permitted the forced removal of First Nation people from reserves near towns of 8,000 or more without First Nation consent).

In the early 1883s, Indian agents began deliberately cutting down food rations to pressure the “Bobtail People” to stay on their reserves and conform to government demands and led to widespread starvation. At the same time, first settlers started obtaining permits to take timber and claim squatter’s rights on the north side of the “Bobtail People” Reserve.

The Canada’s policy of starving forced Chief Bobtail to sign in 1877 an adhesion to Treaty 6 at Blackfoot Crossing as the on behalf of the Muskwacîs area ("Bear Hills/Hobema”) that later became Ermineskin, Samson, Louis Bull and Montana Cree Nations. The adhesion was made to the terms of Treaty 6, which included “provisions for reserves and agricultural supplies to help bands transition to a farming lifestyle”.

Records indicate that Bobtail initially requested a reservation on the Upper Bow River but was refused by the government. His second choice, Pigeon Lake area, became the location for his band's reserve lands. His son Piché, Coyote (Mescakanis) was present at the adhesion to Treaty 6 signing.

Because being associated with and joining Chief Big Bear resistance to the numbered treaty process, in spring 1885, Piché, Coyote (Mescakanis), along with his wife Kakokikanis(Hanger-on) and 21 years old blind daughter Isabelle, were on its way to Montana, pursued by "Steele's Scouts," an Alberta’s civilian militia formed by cowboys and ranchers.

Once receiving false information that his son was killed by the militia and Chief Bobtail grand-daughter is in jail, some of the “Bobtail People” expressed anger and started looting Hudson’s Bay trading post. This criminal rather than political incident cost Bobtail leadership, treaty status and right to stay in reserve, which was bearing his name.

With the Bobtail departure, the band at Muskwacîs split. His younger brother elected himself as Chief of Ermineskin Band. Their brother-in-law, Samson, established his own Band. Soon after, Louis Bull let the Ermineskin Band know that he was having his own band. According to historical documents, in 1886, Chief Bobtail was seen living on Blackfoot Reserve near Pincher Creek with his new wife.

Back at Muskwacîs every branch of Piché family is naming newborn girl Isabelle, after Bobtail’s favorite granddaughter.

“The Dirty Canadian Baggers”

While staying in Montana, Coyote is taking Waskathe (Walking Alone or Walking-in-a-Circle) as his second wife. For next 10 years, led by Chief Little Bear, the young son of Chief Big Bear, having neither the home nor the country, homeless and helpless and hungry, the family wanders through Montana. The local newspapers often describe them as “The Dirty Canadian Baggers”. In 1896 the United State Congress ordered their removal from Montana and delivered the group in cattle cars to the Canadian border in Cutts including Coyote, Isabelle Piché and her husband Apitchitchiw (Shorty Young Boy). At the border, Chief Little Bear was arrested, tried and acquitted due to lack of evidence for his participation in the 1855 Frog Lake incident and no charges were laid. After release from jail, he arrives at Muskwacîs ("Bear Hills" /Hobbema) and joins the rest of the group on the “Bobtail Band” land. That year Montana Band was born.

Unable to support themselves at Muskwacîs/Hobbema, Coyote, Isabelle Piché and her husband Apitchitchiw (Shorty Young Boy), moved to Calgary in 1898 and in the fall, with the help of Isabell’s grandfather Chief Bobtail friend, they settle on Peigan Reserve where they start gathering the firewood in the foothills and selling to settlers. But it was the location near the Oldman River, next to Piché, Coyote (Mescakanis) friend teepee, where the next son was born on cold and snowy November 7, 1898, night. That night both parents did not realize that in 59 years, their son would be asked to lead the Ermineskin Band on rolling Muskwacîs ("Bear Hills" /Hobbema).

Years after their son Robert was born, Isabelle travelled North to introduce her newborn son to ailing father as the Government allowed his return to see the land and meet his “Bobtail People”, for the last time.

“Naming ceremony was arranged and a fest to which all the elders were invited. Chief Bobtail held his one-year-old grandson in his arms and started singing a secret song. Then he started to smoke a pipe and blessed his grandson, at which point Isabell announced that she wished to name the child Keskayo after her grandfather. All the people there agreed that the choice was good. Chief Bobtail then passed his grandson to his younger brother Ermineskin, who blessed the child and repeated the name, Keskayo, over. From there the baby was passed the child clockwise around the teepee, from elder to elder, each of them giving his blessing and calling out his name”.

Chief Smallboy: The Pursuit of Freedom, author Gary Botting

In 1909, the Canadian Government declared the Chief Bobtail (Piché) Band as extinct.

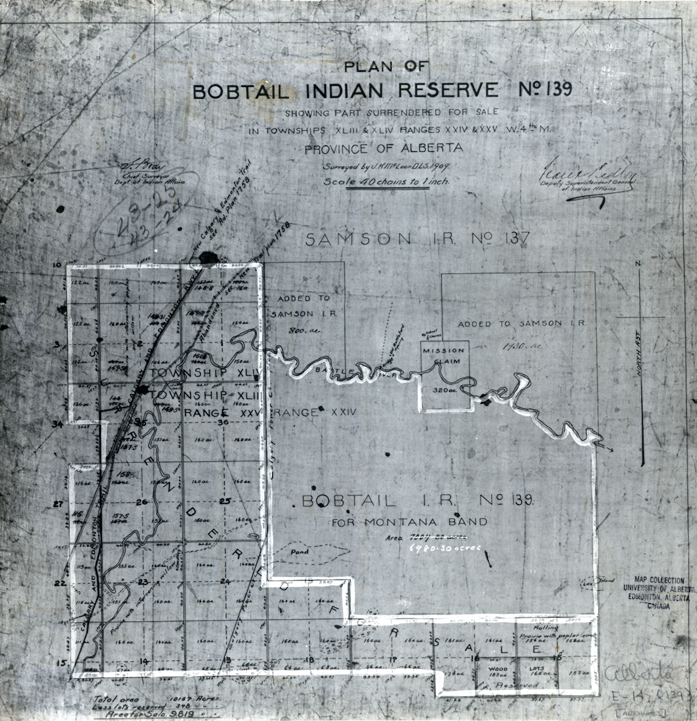

Chief Bobtail Land for sale

Bobtail Reserve land open for sale to soldiers

Forever alien

At the birth they gave him a name Keskayo (Bobtail) after his great-grandfather who was the Chief of the Western Cree bands and who later refused to sign the Treaty 6.

His great- great-grandfather was Chief Louis Piché, a Metis who was a guide to the Hudson’s Bay Governor when he travelled to Upper Bow River Valley. In his honor, the governor named the lake as a "Lake Peechee". Today, this lake is known as Lake Minnewanka and a nearby mountain bears his name and is called Mount Peechee.

On his mother's side, he was a grandson to Chief Rocky Boy, whose reservation in Montana is named after him. His paternal grandmother was a younger sister of Chief Big Bear.

At his time, when growing on the traditional land of his ancestors, oil production became significant and widespread on the reservation where later he become a Chief where, not that long before he was born, the last free-roaming bison were seen on the surrounding rolling hills and once the bison were gone, the hills where the first missionaries started passing by.

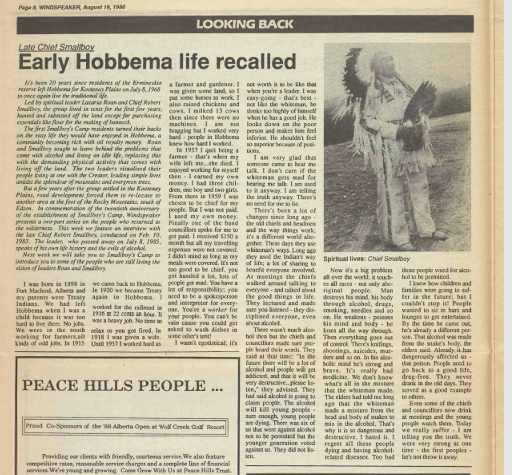

When as a Chief, on his reservation, alcohol quickly reduced and eroded the native spirit and traditional way of life as the "big oil money," brought the opportunities, severe challenges and threats to sovereignty and his Chief’s leadership.

Once realized he couldn't help his Ermineskin people anymore, he and other 25 families left Maskwacis (Hobbema) rolling hills and moved into his ancestors traditional hunting grounds and mountain wilderness of Northern Saskatchewan River Valley to as he always like to say, “Live in Peace”.

Their departure from start was met with doubt, mockery, and a sense that their efforts were pointless and were labelled by most as the "break-away band".

Every winter they were overcoming challenges and enduring hardships of the Kootenay Plains but all of this only helped the group to build character and spiritual strength.

After a few winters, perception, doubt and mockery have changed to respect. This is how the 73-year-old chief has become a venerated symbol to all North America Native people.

Before the majority of the Kootenay Plains Sacred grounds were flooded to make space for a hydroelectric dam, he and his people were forced to move out to place what they start to call “The Smallboy Camp” that soon after becoming the symbol of Indigenous sovereignty and self-determination until he died on July 8, 1984.

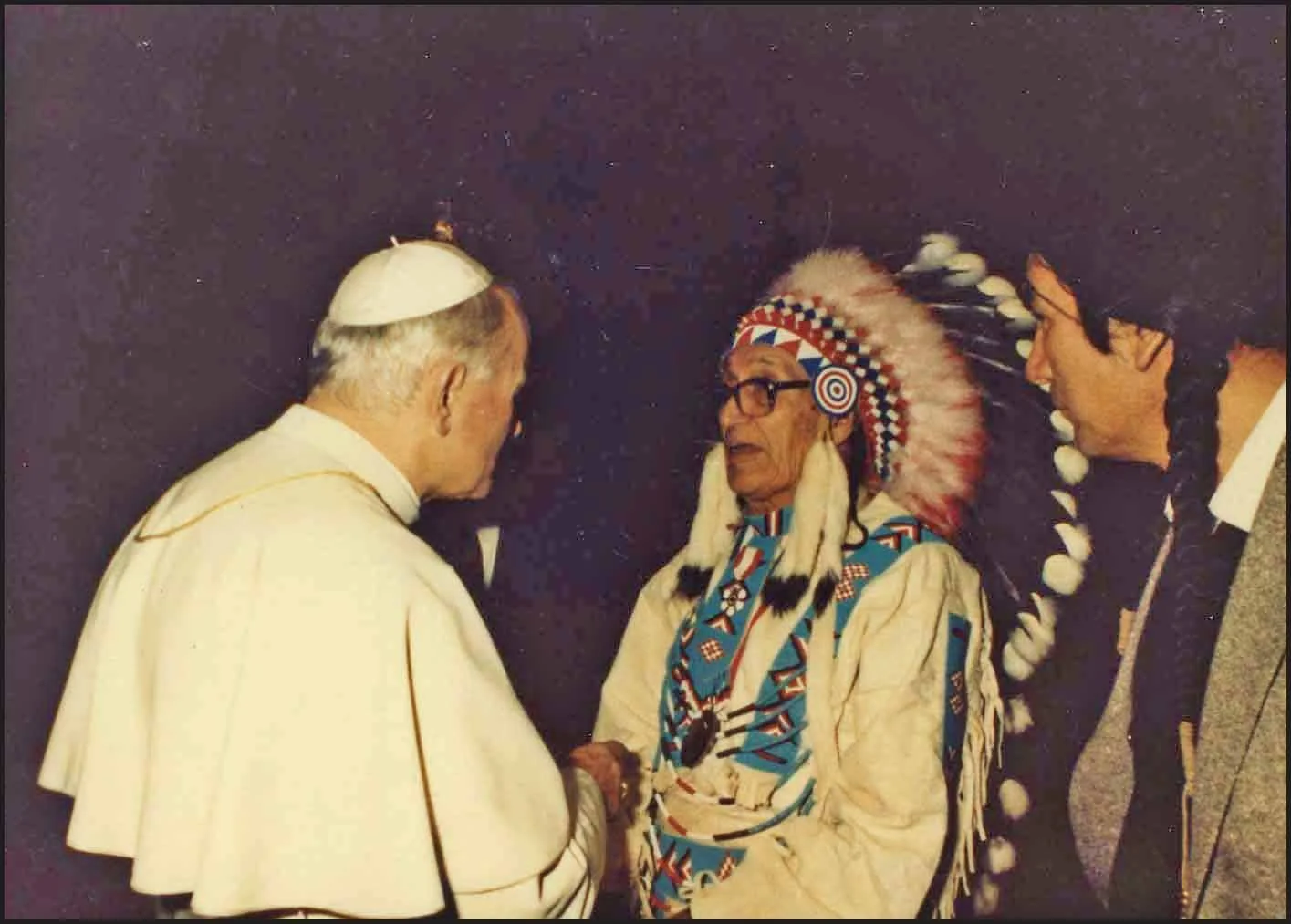

During his life, he travelled to Rome and met Pope John Paul II, to seek help in addressing issues and preserving his people's cultural and spiritual heritage. In London he wanted to meet Queen Elizabeth II to address the land ownership, social, economic, and cultural problems his people are facing in Canada, but Queen Elizabeth II refused to meet him.

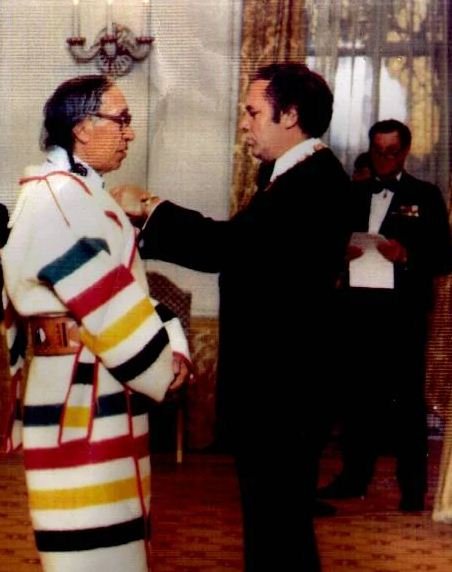

On December 31, 1979, he was awarded the Order of Canada for the “recognition of unique services to his people”.

On July 25, 2022, Pope Francis received a traditional headdress after apologizing for the Roman Catholic Church’s role in the residential school system.

Chief Robert Smallboy meeting Pope John II in Vatican

Chief Robert Smallboy receiving Order of Canada

A Sacred Place

Located near what is today Banff National Park, the traditional hunting grounds on the Kootenay Plains and the whole North Saskatchewan River Valley were not included in any numbered Treaties and this land was always regarded as a Sacred Land by the Ktunaxa, Peigan, Cree and Stoney.

When in 1968 Chief Robert Smallboy set up the camp and his people started to pitch the first teepees, not a long distance from them, the small group of 7 Stoney families already were enjoying their simple wilderness life and calling 5 hectares of their reserve land their home not as 23,680 ha it was promised to them before Alberta took ownership of this land and realized that there oil and coal lays below them.

Chief Robert Smallboy moved out from Muskwacîs ("Bear Hills" /Hobbema only to escape the social and political issues of the reserve and to preserve traditional Cree values and practices as much as the Stoney families who moved to this region under the leadership of Peter Wesley (Ta-Otha) a few years before he was born

For both groups, hunting was a cultural practice that their ancestors used to solidify the friendships and alliances they built.

Alexander Morris and Chief Big Bear (Mistahimaskwa) were central figures in the negotiation of Treaty 6. Morris represented the Canadian government and the Big Bear represented “Cree and the Stoney (Assiniboine) hunting on the Great Plains”.

Once the government realized Big Bear resistance to signing the treaty and settling on a reserve, the Government decided to split Stoney from Cree and moved them to Treaty 7 and labeled Chief Big Bear as a “troublemaker”.

The Treaty 8 when concluded did not consult any of these who were using land located in the foothills of Canadian Rockies. At that time, the First Nations people thought that the treaty was about sharing the land and guaranteed their right to their traditional way of life forever, while the government interpreted it as a complete surrender of the land.

When reading and listening today to land acknowledgments, these are lacking genuine empathy or understanding of history. They just become a "checkbox" exercise for many to appear politically correct without making real commitments.

Dough

For those who would like to see where the Rockies ends, they must travel to Sangre de Cristo (Blood of Christ) mountains located in southern Colorado and northern New Mexico.

It was the 70’s when the North Saskatchewan River Valley and Bighorn Wilderness became the beginning laying groundwork for a “new world order” to save the earth from environmental degradation. This ambitious plan and vision continue to be discussed till early 90’s on 63,000-acre ranch in the San Luis Valley on the edge of the Sangre de Cristo mountains with Rockefeller, Kissinger, McNamara, Trudeau, Moyers, the Dalai Lama, Shirley MacLane and Chief Robert Smallboy along with countless other dignitaries, politicians, businessmen, media moguls, actors and actresses.

Today the estimated annual value of tourism in Banff National Park is over $3 billion. The park continues to see a surge in visitors and this World Heritage Site is on the edge of collapsing and it is Alberta Government that is looking to reduce pressure on Banff National Parks and introduced long-term provincial tourism strategy, with a goal of growing the province's visitor economy to more than $25 billion in annual visitor expenditures by 2035. The strategy identifies locations like the Kootenay Plains and North Saskatchewan River Valley as key areas for future growth.

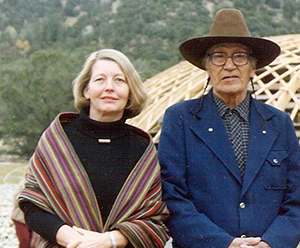

Chief Robert Smallboy with wife of Mourice Strong, Hanne Strong who he adopted as a daughter.

Respect

Before this land was colonized, hunting was far more than a subsistence activity; it was an integral part of daily existence, spiritual practice, foundation for cultural identity and a belief that the land is a sacred, living entity that cannot be "owned" by any individual, but rather cared for and respected by all.

Each of my visits to North Saskatchewan River Valley and Kootenay Plains is spiritual and the reasons for connecting with mountain environments where I can emphasize on mental balance, respect for the land's history, and a reverence for the sacred.

Show kindness and respect to me, this is only one thing that I am asking and expecting from you, when working toward seeing this Sacred land be free from any commercial development.

You are always welcome to join me in this effort.

Hiy hiy,

Isniyés,

Siksiksimasiituk,

Thank You,

Merci,

Dziękuję,